In 1807, an act was passed to establish a grammar school in each of the eight districts into which the province of Upper Canada was then divided. It was also provided that the sum of 100 pounds be paid annually to each teacher in these schools.

The Thorold people were quick to profit by this act, and by 1817, there were nine public schools in the township. There are no official records in existence by which we may ascertain just where these nine schools were situated.

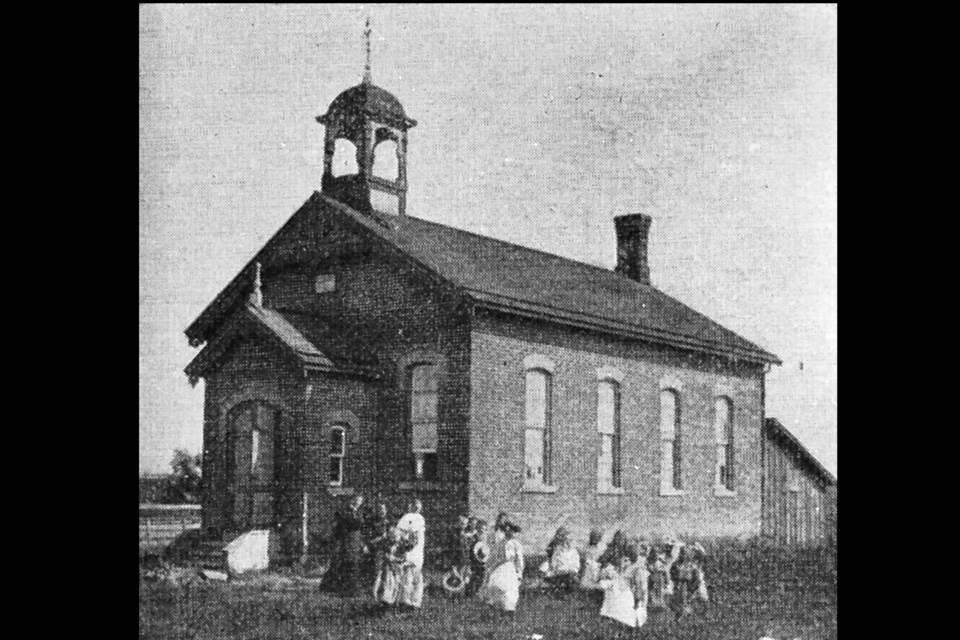

The DeCew Falls School is known to be one of the oldest, while Street’s school at St. Johns (later used as a grocery), Hoover’s School near Centreville, and the Wilkerson school near Beaverdams were probably among those established in 1817. Another was probably the old log school on the Chippawa Creek.

The first school houses were primitive log buildings with the desks ranged around three sides of the room. The pupils were seated facing the wall, for in those days very little attention was paid to the physical comfort of the young. The people had to adapt themselves to circumstances, and the boys and girls were considered fortunate in having attention paid to their mental development.

There were no inspectors to see that the light came from the proper direction, or that the seats were adapted to the requirements of the younger pupils, or even to make a report upon the quantity and quality of the knowledge instilled into the youthful mind. Young children then sat all day long with the light streaming in their eyes, and with no support for their backs. The seats were slabs, placed with the flat side upwards and very unsteadily supported by wooden pegs driven into their rounded surfaces underneath.

Frequently, a little variety was created in the day’s proceedings by the collapse of these seats, which thus served a good purpose in keeping the school from the deadening effects of mere mechanical routine. In many cases, no doubt, their minds were really educated by conscientious and enthusiastic teachers, but often they were considered as mere receptacles for a mass of unrelated knowledge.

In the small township schools, the first masters were discharged soldiers who had served in the War of 1812. Many of these taught very indifferently, but in occasional instances we find that they cultivated in their pupils an ardent love for arithmetic. “Your sums, lads and lasses,” was the favourite command of one of these old teachers at the Beaverdams School whenever he felt that his supply of learning in the other branches was falling short of the demand.

Books were exceedingly scarce in those days, and there was no attempt made to have all the pupils use the same series. Cobb’s and Murray’s spelling books were both used. The Bible was the chief text book for reading. The ink used was made by the pupils themselves, usually from oak galls or soft maple bark; the pens were the old-fashioned goose quills. The text-books were all printed either in England or the United States, and in geography and history, which were taught only to advanced pupils, a boy was likely to know as much about Spain or Italy as his own province.

Gradually, the schools improved, with the general progress of the country. Physical infirmity ceased to be sufficient proof of a teacher’s scholarship, and the disabled soldiers gave place to the “peripatetic teacher,” who rarely stayed in any one school longer than a term.

Only a small proportion of the salary came from the government grant, so the remainder had to be made up by subscription. During the summer months, the instructors were usually women, who received, besides the grant, about $1.50 per quarter from each pupil, while they “boarded around” in the school section.

In the winter, men were employed, but their salaries were larger, since they nearly always charged each pupil a fee of $2 a quarter. These old-time pedagogues naturally made themselves as indispensable as possible in the more comfortable houses, but in a populous district they often had no settled abode, as each parent had to give during the term only from three to five days’ board in addition to fees, as a return for the tuition of each child sent to the school.